Making the cut: is cross-laminated timber safe?

By Paul Hargest

TORONTO, Aug. 23, 2018 /CNW/ – Last March, part of a floor under construction at Oregon State University collapsed after it became ‘de-laminated’ (unglued) at one end. It was a 4- by 20-foot panel of cross-laminated timber, or CLT. Ironically, it was part of a new building that will house the university’s College of Forestry. While no one was injured, the incident has raised questions (again) about the risks of CLT.

CLT is a type of ‘engineered’ or ‘manufactured’ wood, where two-inch-thick boards of wood are glued and pressed together to form larger wood panels. To make CLT, boards are stacked, one on top of the other, with each layer running at a 90° angle to the one above / below it. This is done to maximize strength.

Developed in Europe in the 1990s, CLT is now being used more in North American construction. While proponents argue that it is strong and environmentally friendly, more people are taking a harder look at its structural performance, its risk related to fire, and the health and safety of occupants within it.

The fact that CLT is glued together raises concerns regarding water. Fire may have a more devastating impact on property, but it’s water that causes the most building damage overall (think flooded basements and leaky roofs). It’s therefore conceivable that a material made with layers of glue could, over years and decades, become unglued.

It’s therefore conceivable that a material made with layers of glue could, over years and decades, become unglued.

CLT is also at risk of structural degradation due to ‘rolling shear failure’, which is cracking within the wood. It happens when CLT panels — usually flooring — are under heavy load-bearing pressure. The pressure causes layers in the panels to break down and separate. Often, they are inner layers, resulting in compromised durability that wouldn’t be visible to occupants.

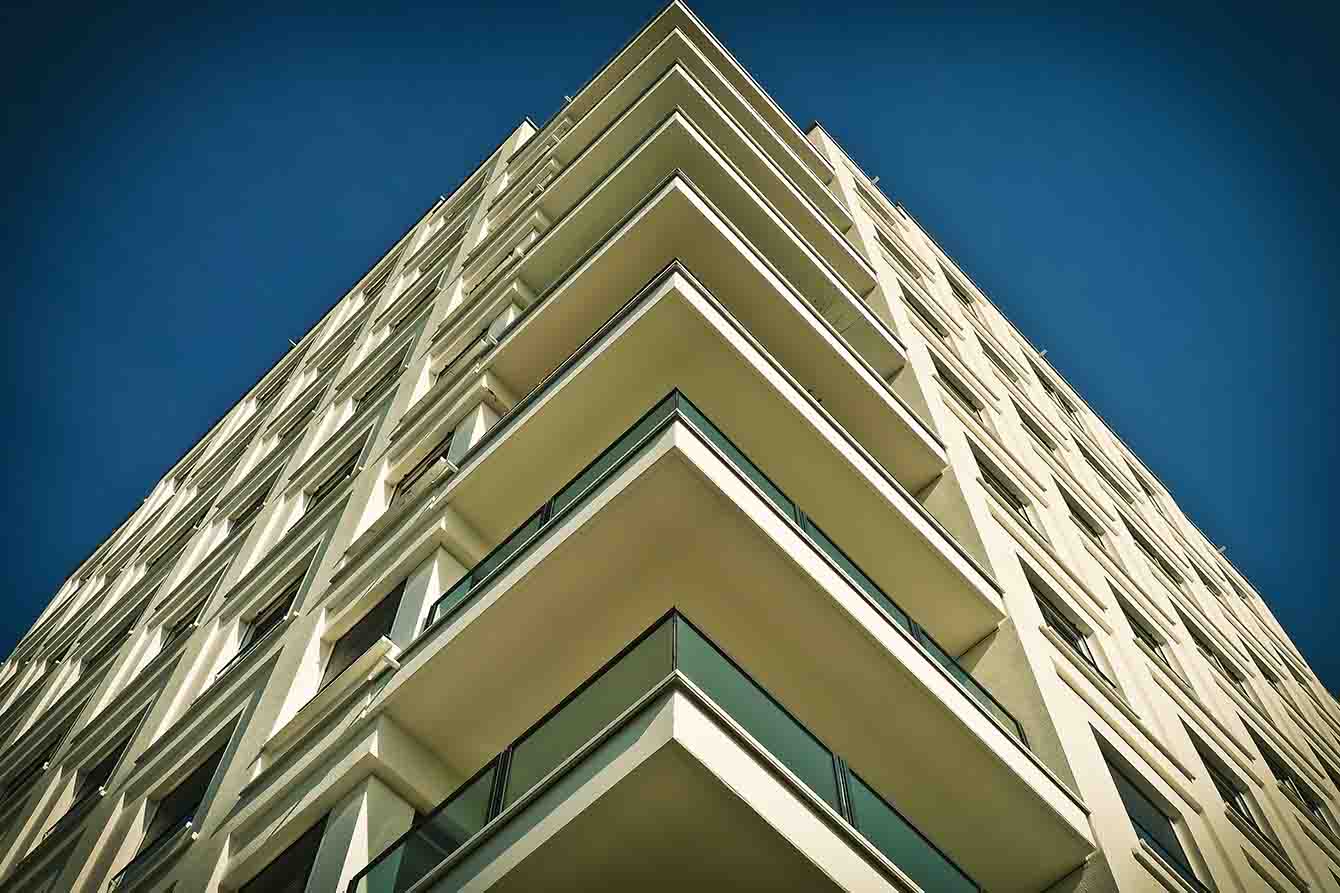

The threat of fire is perhaps the greatest concern surrounding CLT, especially in light of incidents such as the 2017 tragedy at London’s Grenfell Tower, and similar cladding-related fires that have ravaged skyscrapers in Dubai. Building and fire officials around the world are now shining a harsher light on seemingly cost-effective but potentially more flammable building materials.

Today’s building fires are fuelled by an abundance of man-made materials, from foam-filled couches and acrylic rugs to polyester curtains. These materials can burn hot and fast enough to cause floors to collapse in 20 minutes. Which begs the question: Can CLT withstand these conditions?

The consensus among many firefighters is that there hasn’t been enough testing to accurately determine how CLT performs in the real world. And in fact, the International Building Code (IBC) has been reluctant to recognize CLT as a structural material, resisting pressure to increase the maximum number of storeys allowed in CLT-constructed buildings.

The consensus among many firefighters is that there hasn’t been enough testing to accurately determine how CLT performs in the real world.

Now, due to industry lobbying, it appears that codes in the U.S. are moving in this direction.

Regardless, expert bodies such as the International Association of Fire Chiefs (IAFC) are pushing back. The IAFC recently issued a statement rejecting proposed building-code changes allowing CLT in tall wooden buildings. In the statement, the IAFC noted that “the changes are overreaching and lack true technical support for many concepts proposed.”

The IAFC questions a great deal of the assumption made regarding how CLT holds up in real fires. “The fire service has a duty to respond to incidents for the life of the buildings. These proposals appear to not be in full disclosure and lack aspects of technical support and justification for the concept as a whole.”

While the performance of CLT may be in doubt, there have been broader concerns about the testing of wood products in general. In 1999, the UK Timber Frame Association (UKTFA) conducted a study that found timber framing to be fire-safe (timber framing had been prohibited in England following the Great Fire of London in 1666).

The study involved igniting a six-storey timber building in an aircraft hangar. The flames had moved through the first two storeys, at which point firefighters put them out. The UKTFA neglected to say that later that night, the fire reignited. By the time firefighters arrived back at the hangar, all six storeys were, according to BBC News, “completely burned out. Brickwork cracked and the heat was so severe the fire officer evacuated his men for fear the building was about to collapse.”

News of this ‘second fire’ was kept under cover until 2003, “by which time,” says the BBC, “timber framed buildings, which are cheaper to make, were already sprouting over London for the first time since 1666.”

It’s a fact that wood is limited in its ability to resist fire. Now, however, some scientists are also casting doubt on its eco-friendliness.

It’s a fact that wood is limited in its ability to resist fire. Now, however, some scientists are also casting doubt on its eco-friendliness. A recent study — conducted, in fact, by Oregon State University — points to the clear-cutting of forests by the lumber industry as a major cause of carbon pollution. Forests are natural filters that absorb large amounts of carbon; when they are cut, the carbon is released.

One scientist who contributed to the study says “we’ve been giving wood too much credit” as a green building material. In other words, it may be healthier to keep the wood ‘alive’ than to cut it down and build with it. In other words, it may be healthier to keep the wood ‘alive’ than to cut it down and build with it.

CLT has attracted significant negative attention from a health standpoint following controversy that erupted in 2016 over laminate wood products from China. It was discovered that the products, mainly flooring, contained extremely high levels of formaldehyde. Tens of thousands of consumers were affected, and worried homeowners hastily ripped out floors to get rid of it.

In response to the scare, the U.S. Centers for Disease Control (CDC) studied the issue. The CDC’s follow-up report stated: “Our calculations show that if homes already contain new materials or products that release formaldehyde, the new floorboards could add a large amount of additional formaldehyde to what is already in the air from other sources. This additional amount of formaldehyde increases the risk for breathing problems as well as short-term eye, nose, and throat irritation for everyone.”

While manufacturers have worked to address the problem, the fact remains that much of today’s engineered flooring contains some formaldehyde. Formaldehyde is a carcinogenic gas that is released over time. Although it is present in many household materials, ranging from paint to insulation, the potential increase resulting from using CLT within the building can push it significantly higher.

Regardless, entire buildings are being built of CLT, and it is being touted as comparable to concrete in terms of strength and durability. That comparison, however, does not appear to be reflected in building insurance.

A study conducted by Boston College on behalf of the U.S.-based National Ready Mixed Concrete Association found that builder’s risk insurance cost 22-72% less for concrete buildings, and commercial property insurance was 14-65% lower.

Clearly, CLT remains controversial. Concerns related to building strength, fire resistance, and health and safety continue to chip away at CLT, with organizations such as the IAFC publicly opposing its widespread use.

All of which indicates that advocates likely will continue to face resistance — and will have their work cut out for them.

For further information: Marina de Souza, Executive Director, Canadian Concrete Masonry Producers Association, 416-495-7497, info@ccmpa.ca

Recent Posts

Future of Modular Construction Using Concrete and Masonry

These factors collectively position modular construction as a key player in shaping the future landscape…

The Future of Cement as a Sustainable and Resilient Building Product

The future of cement shaping up to forge a more sustainable construction industry that meets…

The Growing Importance of Resiliency in the Design and Construction of Buildings

Resiliency is becoming increasingly important in building design and construction due to the rising frequency…

GCCA Global Low Carbon Ratings for Cement and Concrete

The Global Cement and Concrete Association (GCCA) has developed a standardised low carbon rating system…

Building for Resiliency with Insulated Concrete Forms

Building with Insulated Concrete Forms (ICFs) is increasingly recognized as a critical component of modern…

Building Resiliency in the Pacific Northwest

In the Pacific Northwest, the increasing frequency and severity of climate-related disasters, such as wildfires,…