Keith Porter, Western University

A tornado cut a 270-kilometre path through Kentucky in mid-December 2021, killing 80 people, many in their homes or workplaces, and rendering thousands homeless. The incident prompted David Prevatt, a professor of structural engineering at the University of Florida, to write an opinion piece for the Washington Post, reminding Americans that new buildings could be tornado proof, but are not.

We are learning similar truths in Canada. Barrie, Ont., struck by a set of tornadoes on July 15, 2021, is still recovering. So too, are those who survived the fires in Fort McMurray, Alta., in 2016, and in Lytton, B.C., in June 2021. It’s the same story following the floods in British Columbia in November 2021 and the derecho that struck Southwestern Ontario in late May, lifting roofs off some buildings and destroying others.

Engineers, architects and builders can design and construct affordable new buildings that can resist tornadoes, floods and wildfires without making the buildings into bunkers. We could also design earthquake-resilient buildings, but do not.

I am a structural engineer and an expert in performance-based engineering and catastrophe risk management. I believe the only way to make that happen is to require our building code to minimize society’s total cost to own new buildings. We have always been free to make that happen, but have a rare window now to shape that future, as the nation and code developers urgently respond to the climate crisis.

Why don’t we build resilient buildings?

Building-code writers, engineers and others frequently tout the benefits of modern building codes. But new buildings only keep us relatively safe; they’re not disaster proof. Why don’t we build better buildings? Because it would cost a little more.

We build to minimize initial construction costs while maintaining a reasonable degree of safety and avoiding damage where practical, a strategy known as “least-first-cost” construction. We save a small amount on initial construction costs and call the savings “affordability.”

But that kind of affordability is an illusion, like a tantalizingly low sticker price on a flimsy car. Wise car buyers know that the low cost is just the beginning of a series of bills.

In new construction, every dollar saved weaves in $4 or more of future costs to pay for unpredictable catastrophes: severe storms, massive earthquakes and catastrophic wildfires. That future cost is not an if, but a when — or rather a sequence of whens made more frequent and severe by the climate crisis.

In research for the U.S. Federal Emergency Management Agency and others, my colleagues and I applied simple methods to design buildings to be stronger, stiffer, or above the flood plain than the U.S. building code currently requires. (Canada’s National Building Code is similar.) We found that society would initially pay about one per cent more for new construction, but avoid future losses many times greater, minimising society’s long-term ownership cost.

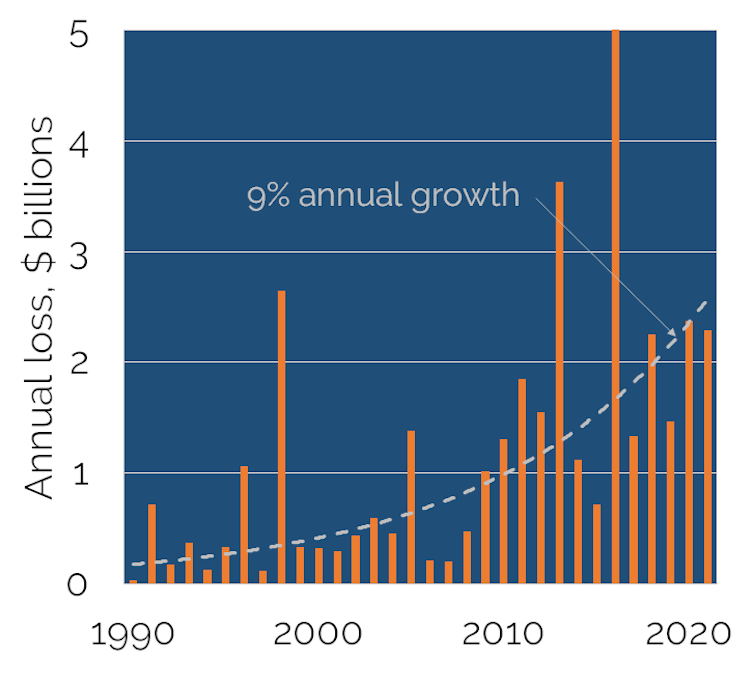

Engineers could have used these ideas long ago. If we had, Canada wouldn’t be losing over $2 billion annually to natural catastrophes, equivalent to the cost of four days of new construction.

Our losses grow nine per cent every year, like a credit card that gets charged more each month than is repaid. But unlike a credit card bill, nature demands an unpredictable, enormous payment any time it wants, from anywhere in the country. No Canadian community is immune.

Author provided

We can fix the problem

Prime Minister Trudeau has committed to bold, fast action on climate change and its associated disasters, and better building codes can be a part of it. We could install sewer backflow valves in homes and workplaces, use non-combustible siding rather than vinyl in the wildland-urban interface (where the built environment mingles with nature) and install impact-resistant asphalt shingle roofs in hail country. Engineers have long lists of ready-made solutions both for new buildings and the ones we already have.

Building codes created those problems. They aim for safe and maximally affordable construction, and ignore long-term ownership cost. We build cheaply but not efficiently.

Three fatal tornadoes in 15 years convinced city officials in Moore, Okla., that the national building codes weren’t protecting them. So, they enacted an ordinance to make new buildings resistant to all but the most severe tornadoes.

Developers warned that the stricter requirements would drive up home prices and that development would dry up or move outside Moore. Neither thing happened. A few years after the ordinance passed, researchers found no impacts on home prices or development.

Other jurisdictions could do better too, just like Florida did after Hurricane Andrew in 1992. The state leapt ahead of U.S. building codes with its own stricter, more cost-effective code. The Insurance Institute for Business and Home Safety developed a voluntary standard, called “Fortified,” that reduces future losses and more than pays for itself in higher resale value.

Disaster-resilient buildings that also cost less

The climate crisis is forcing major energy-efficiency changes to the building code, offering a rare opportunity to fix our growing disaster liability and minimize long-term ownership cost. The update might include these three steps:

- Enact a building code objective to minimize society’s total ownership cost of new buildings. The Canadian Commission on Building and Fire Codes could formalize the principle in the National Building Code of Canada.

- Require code-change requests (proposals people make to the Canadian Commission on Building and Fire Codes for inclusion in the National Building Code) to be accompanied by estimates of added construction costs and benefits in terms of reduced energy use, future repair costs, improved health and life safety outcomes, and other economic effects whose monetary value can be reasonably estimated.

- Limit the freedom of code committees to reject cost-effective code-change requests.

Such changes will eventually shrink Canada’s disaster credit card balance. While Canada rethinks energy efficiency, it can also tackle the false economy of least-first-cost construction. With slightly greater initial costs, our buildings will be better able to survive disasters and cost less to own in the long run.

With a wiser code, we can have better, safer, more efficient buildings for ourselves, our neighbours, our children and all future Canadians.![]()

Keith Porter, Adjunct research professor, civil and environmental engineering, Western University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.